Blog

Hidden Plymouth, Route 2 - Millbay Mini

I’m slightly overwhelmed by how well Route 1 has been received I have had some lovely feedback and suggestions for future routes. One such suggestion is to do something shorter that children can take part in, so where better than around Millbay. I can test it with my own kids as they go to Plymouth School of Creative Arts which is the starting point for this route.

There are loads of quirky little features in and around Millbay, its relatively flat and the route is only 2km. If the walk doesn’t wear the little ones out, West Hoe park is within walking distance too. The route starts outside the school and if you are driving there are three car parks nearby, Martin Street, the Pavilions and Brunel Way. Unfortunately they are all Pay and Display.

Points of Interest

Octagon Brewery

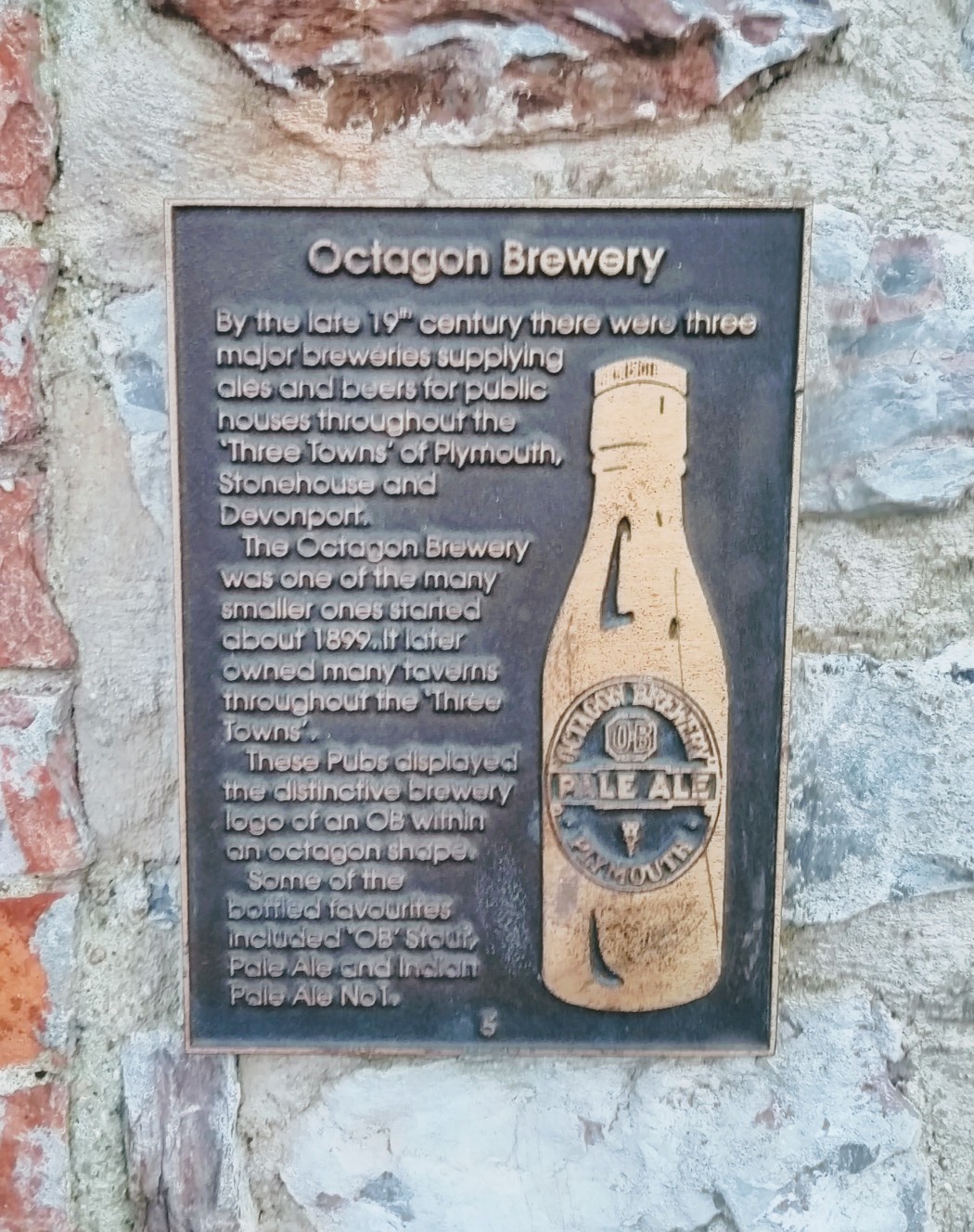

From the school head the short distance up Martin Street to the junction with Sawrey Street, here you will find the old Octagon Brewery, now Docwra Bros. car body shop. The brewery was founded in 1861 and incorporated in 1899. It continued until 1954 when it was sold to H&G Simonds. The following year the company was liquidated. On the side of the building is a small plaque:

Octagon Brewery

By the late 19th century there were three major breweries supplying ales and beers for public houses throughout the ‘Three Towns’ of Plymouth, Stonehouse and Devonport. The Octagon Brewery was one of the many smaller ones started about 1899. It later owned many taverns throughout the ‘Three Towns.’

These pubs displayed the distinctive brewery logo of an OB within an octagon shape. Some of the bottled favourites included ‘OB’ stout, Pale Ale, and Indian Pale Ale No 1.

The distinctive logo can still be seen today in the windows of the Dolphin Hotel on the Barbican, one of Plymouth’s most popular pubs.

The Phoenix

Just a short distance up Sawrey street is the Phoenix Tavern, alas no longer a tavern. The closed pubs project has some interesting pictures of the pub in the 1930’s. On the side of the building is another interesting plaque.

Phoenix Hall Roller Skating Rink.

Roller skating took England by storm and by the late 19th century Plymouth had half a dozen rinks. In May 1880 the Phoenix Hall Rink was one of the last to open. Another rink, Pavilion New Skating Rink was located nearby in Martin Street.

Various skating prizes could be won. These were usually silver cups or medals but, on special occasions, prizes could even include live chickens or a pig to take home!

Millbay stars

From the Phoenix Tavern walk back south down Phoenix St and cross Millbay Road. Head back towards the mini roundabout at the entrance to Millbay docks on the wall you will see a number of Hollywood style stars. These show all the famous people who have berthed in Millbay, the vessel they arrived on, and the year. The stars include:

- Walt Disney, Normandie, 1935.

- Charles Laughton, Champlain, 1935.

- Gloria Swanson, Queen Mary, 1938.

- Jack L Warner, Queen Mary, 1938.

- Maurice Chevalier, Manhattan, 1938.

- Sabu, Paris, 1938

- Laurence Olivier, Ile de France, 1939.

- Vivien Leigh, Ile de France, 1939.

- Gene Autrey, Manhattan, 1939.

- Boris Karloff, Italia, 1950.

- Judy Garland, Ile de France, 1951.

- Charlie Chaplin, Mauritania, 1951.

- Alan Ladd, Ile de France, 1952.

- Bing Crosby, Liberte, 1952.

- Sarah Vaughan, Liberte, 1953.

- Lena Horne, Liberte, 1956.

- Duke Ellington, Ile de France, 1958.

Gold bullion

At the time of writing the ‘Gold’ bullion statue has been removed whilst a new retirement home is built on adjacent land, however it will be restored so is worth a mention for the future. The statue commemorates the practice of storing large quantities of bullion in the open on the dockside with a single policeman to guard it. This was common in the 1930’s with gold being sent to and from America, Australia and South Africa from the docks.

Between 1932 and 1934 over a million pounds of gold and silver ingots and sovereigns were landed at the docks following the groundbreaking salvage from the P&O liner ‘Egypt’’ which sank off the coast of France in a decade earlier in 1922.

Endurance Blue Plaque

From the gold bullion head east down Millbay road to Isambard Kingdom Brunel Way, turn right and head up it. At the time of writing there are hoardings up along the road with interesting Plymouth facts on them.

At the end of the road you reach Millbay docks where you will find a memorial stone and blue plaque commemorating Ernest Shackleton setting sail onboard the Endurance on the 8th August 1914.

After Roald Amundsen’s success reaching the South Pole in 1911 (and the subsequent death of one of Plymouth’s most famous sons, Robert Falcon Scott) Shackleton was aiming to complete the grandly titled ‘Imperial Trans-Antarctic expedition’, crossing Antarctica from one side to the other.

The expedition came into jeopardy when the Endurance became trapped in the sea ice, and was ultimately crushed and sank in the Weddell Sea. The 28 man crew found themselves stranded on the pack ice with no hope of rescue. They camped on the ice for 6 months drifting slowly northwards. Eventually the ice became too unstable and the crew were stranded on the small uninhabited Elephant Island after taking to the ships boats.

Shackleton and 5 of his crew then rowed 800 miles to South Georgia island in their 22.5 ft boat the ‘James Caird’. They were aiming to seek help from whaling outposts on the island and to come back and rescue the remaining 23 men. The journey was gruelling, through heavy seas and freezing conditions but after 14 days they successfully reached the island.

It would be a further 3 months before Shackleton would be able to rescue the men he left behind, due to the start of the southern winter. The government of Uruguay loaned him a ship to affect the rescue and amazingly all 28 men of the ‘Endurance’ survived.

West Hoe Road signs

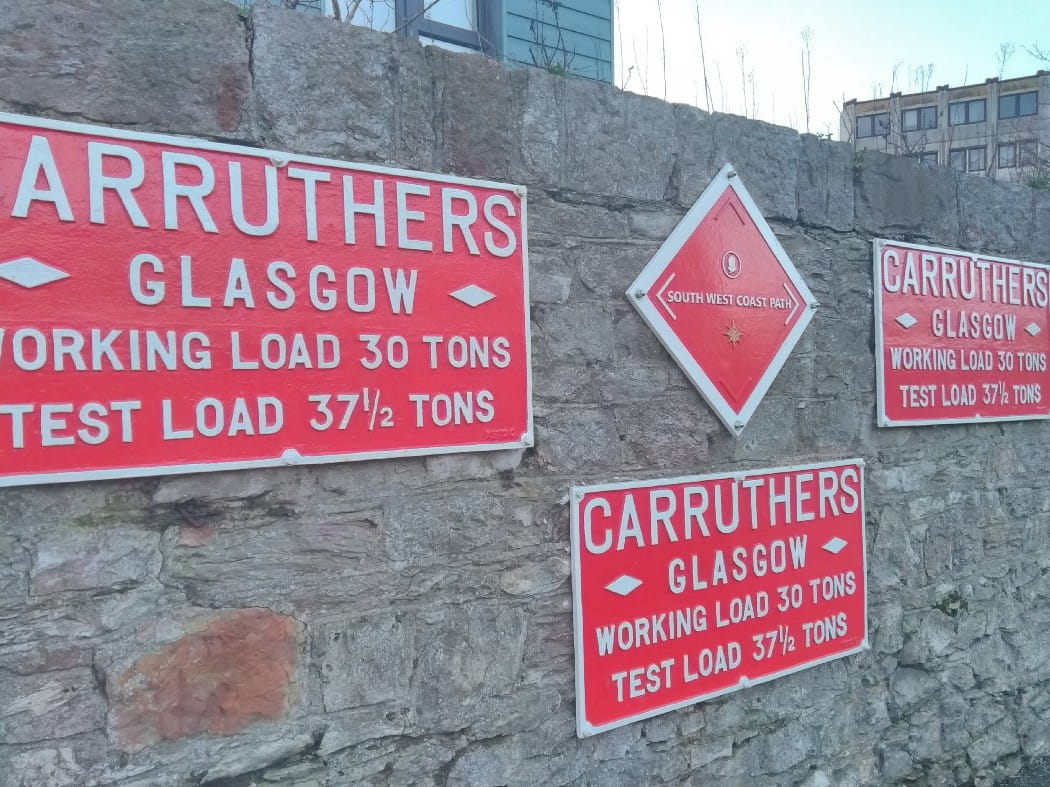

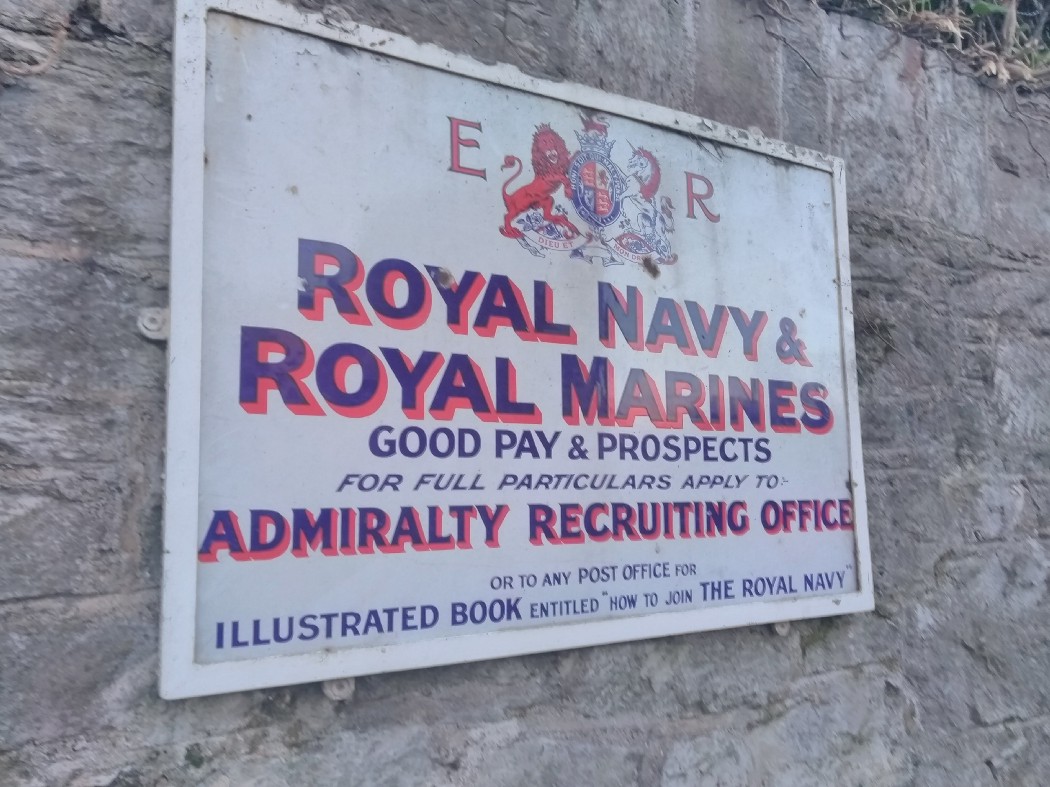

From the docks head up the 35 steps (count them with the kids) from Willoughby Way to West Hoe Road. You will find many old signs on the dock boundary wall. These are reclaimed signs from businesses and facilities in the docks. We only managed to find the Carruthers cranes and Royal Navy and Marines recruitment signs. Apparently there is also Singer sewing machines sign from the sailmakers, and ‘Armstrongs’ which used to be on the rail bridge at the docks mouth.

Millbay docks

Millbay takes its name unsurprisingly from being the site of tidal mills as early as the 12th century. The docks however really took off in the 19th century. Millbay pier was built in 1844 and the following year the SS Great Britain berthed here during her maiden voyage to New York.

In 1846 the Great Western Dock company were granted an act of Parliament to provide full facilities for shipping in the docks. Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed the new docks and the majority of the original dock walls survive today.

Millbay quickly became a busy commercial dock and by the 1870’s started to become a busy terminus for trans-atlantic visitors. It was known as the ‘route that cuts the corner off’ as passengers could disembark at Plymouth and get a fast train to London, thus avoiding the longer sea journey to Southampton or Tilbury. In the early 20th century 6 million passenger landed or embarked for America from the docks.

In 1912 the surviving crew of the Titanic landed at Millbay docks in secrecy and were taken by train to Southampton. There is a memorial inside Millbay marina, however it is not accessible to the public.

Today the docks are undergoing major regeneration new houses and flats have been built, the school, and King point marina (including the lovely Dock Restaurant) have also been developed.

Building continues with the second phase of homes and retirement apartments underway, plus proposals for a hotel and shops are out for public consultation.

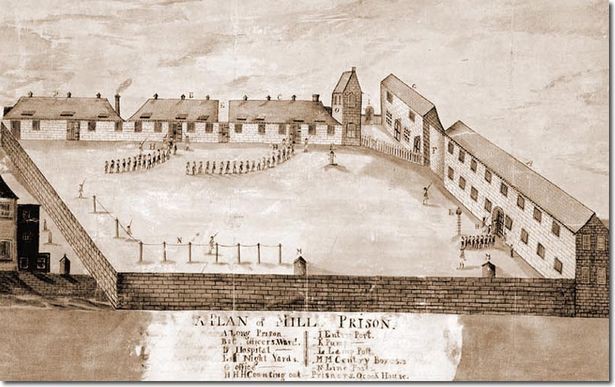

Millbay Park

As you continue along West Hoe Road, there is a strangely shaped park on the Eastern side of West Hoe Road. The park is terraced with a football pitch at the peak, the flat space gives away its use as a barracks between 1845 and 1856. Before this however, the area was a gaol for prisoners of war. Initially it was constructed to house 1500 American prisoners of war during the War of Independence (1777–1783).

During the Napoleonic wars the prison held 11,000 French and American prisoners of war. It was at this time in 1806 that the prisoners were marched the 15 miles to Princetown on Dartmoor to build Dartmoor Prison (to contain even more prisoners of war!)

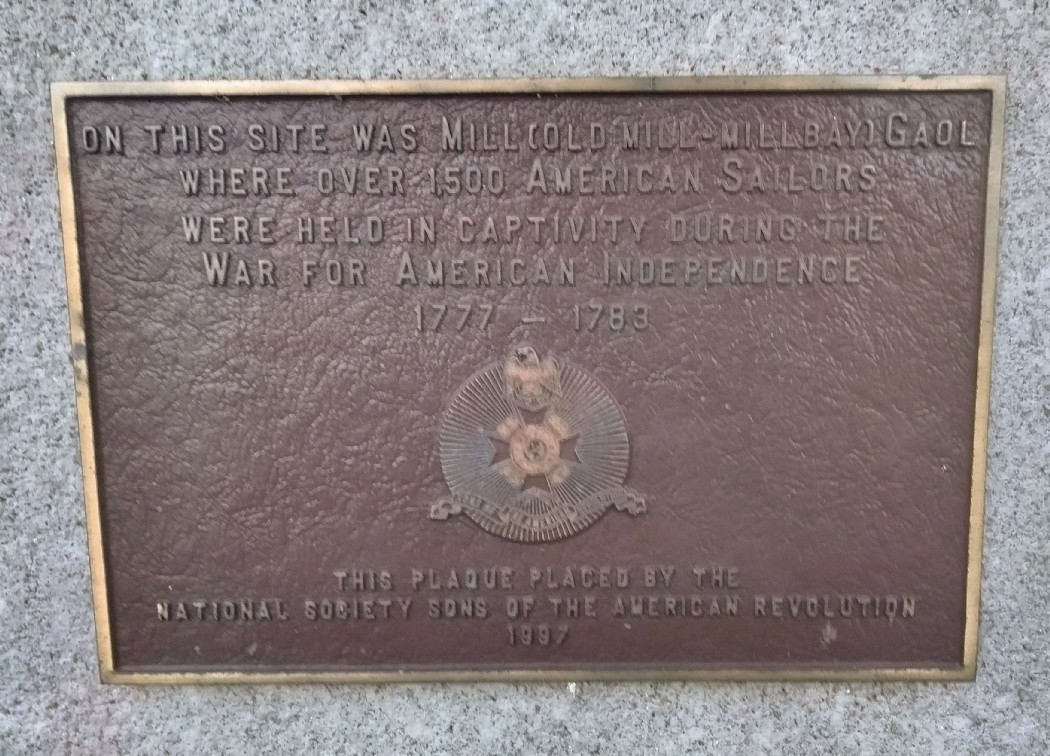

Today little remains of this history other than a couple of plaques on the gates of the park. The first commemorates the first American sailors held prisoner and reads:

On this site was Mill (Old Mill — Millbay) Gaol where over 1500 American sailors were held in captivity during the war for American independence 1777–1783.

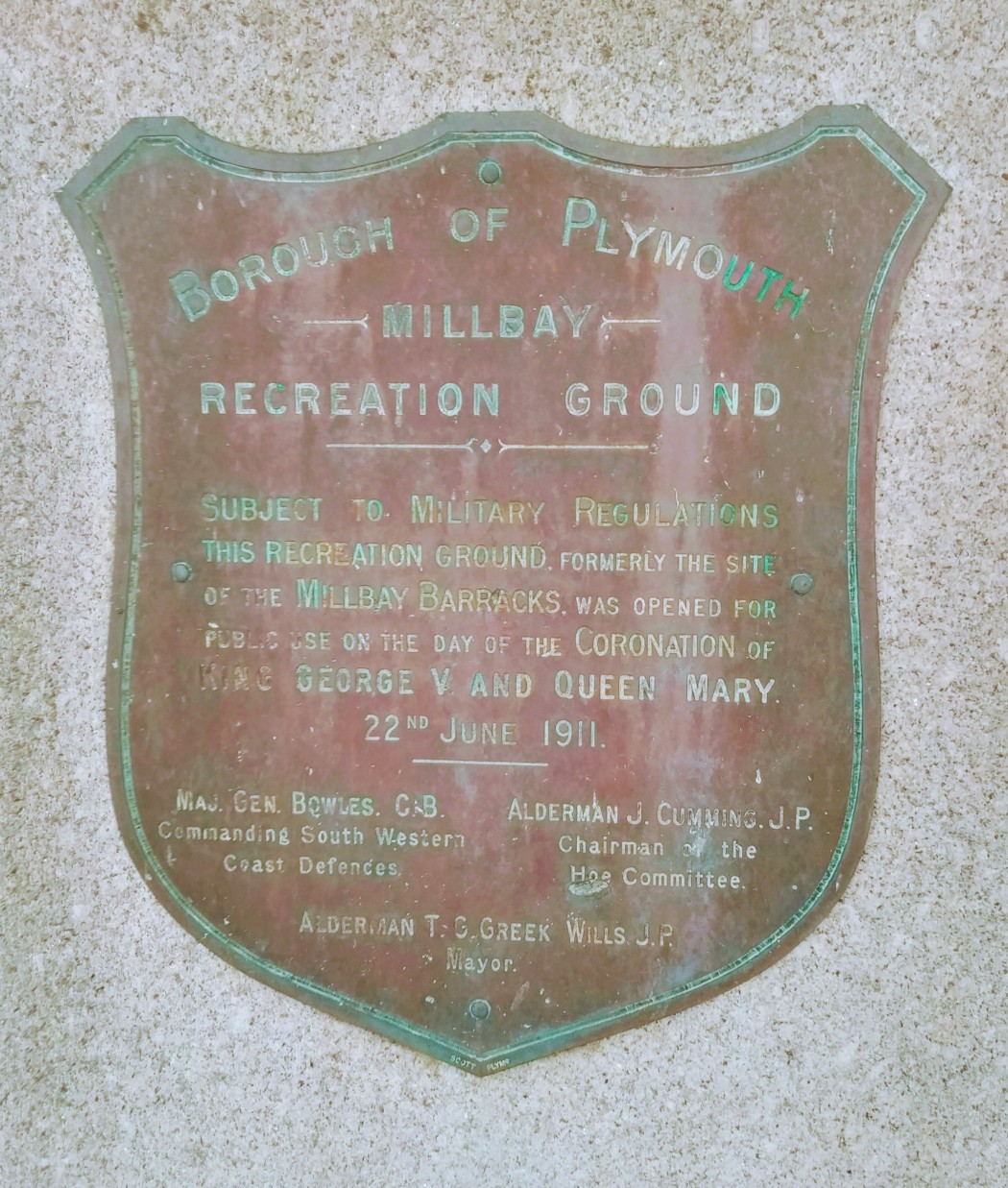

The second commemorates the barracks being turned over for public recreational usage (in a suitably clipped and bossy tone):

Subject to military regulations this recreation ground, formerly the site of Millbay barracks, was opened for public use on the day of the coronation of King George V and Queen Mary. 22nd June 1911.

Eddystone Lighthouse Pavement

Just opposite the park in front of the Salumi restaurant is a paved circle which doesn’t look like much, until you notice the strange shape of the slabs. These are the groundbreaking interlocking patterns of the stone blocks developed by John Smeaton to build the Eddystone Lighthouse.

The interlocking blocks were so successful that the lighthouse stood for 123 years, indeed the rock it was built on wore away before the blocks did forcing it to be replaced. Indeed the lighthouse still stands today proudly on Plymouth Hoe 259 years after it was first constructed.

If you look closely there is a rather grisly plaque embedded in the pavement. It reads:

On the 1st December 1755 fire destroyed John Rudyard’s Eddystone lighthouse. As flames reached the roof of the tower a worker, Henry Hall (aged 84) looked up and managed to swallow a blob of molten metal which lodged in his stomach. He died of lead poisoning twelve days later.

Duke of Cornwall Hotel

The Duke of Cornwall dominates the skyline of Millbay and stands grandly in Victorian splendour. It was Plymouth’s first luxury hotel, the South Devon railway company recognised the need for luxury accommodation as first class travel increased to and from the docks due to the ‘route the cuts the corner off’ mentioned earlier. The hotel’s popularity matched the fortunes of the docks, peaking in the 1930’s.

During the second world war, the hotel was embroiled in scandal as the family running the hotel were strongly tied to the fascist party. Due to Plymouth’s military importance the family were placed on MI5’s suspect list and in 1944 they were forced to leave the hotel before the Allied invasion of France.

In the 1970’s the hotel faced the threat of being pulled down primarily because of the lack of car parking, despite being listed in 1975. Sir John Betjeman helped lead the fight for it’s survival describing it as “one of the finest examples of Victorian gothic architecture he had ever seen.’ the hotel’s future was thankfully secured in 1988 after the terraced garden had been changed to a car park.

Millbay Station (the Pavillions)

Little remains today as a reminder that the Pavilions was once the location of Plymouth’s primary railway station. The only remaining features are two stone pillars outside the main entrance with no real explanation as to what they are or why they are there. They are in fact the posts that made up the forecourt entrance to the station.

The station was built in 1849 by the South Devon railway as the terminus of its line from Exeter. It was originally a 7ft broad gauge railway but was converted to 4ft 8½in standard gauge in 1892 after the Great Western railway had acquired the South Devon in 1876.

In 1941 the station was closed to passengers after being bombed. Traces of cannon damage can still be seen on the posts. In 1969 the station was closed to good trains, apart from through traffic to the docks. Then finally in 1971 the station was closed for good. Twenty years later the Pavilions leisure complex was opened on the site.

From the Pavilions it’s a short walk downhill back to the school. I hope you enjoy the route.