Blog

The OSI Model

Tags: internet, network security, network engineering, network fundamentals

The OSI model is designed to ensure compatibility of network devices (and their operating systems) regardless of manufacturer. OSI stands for Open Systems Interconnection and is defined by the International Standard Organisation (ISO).

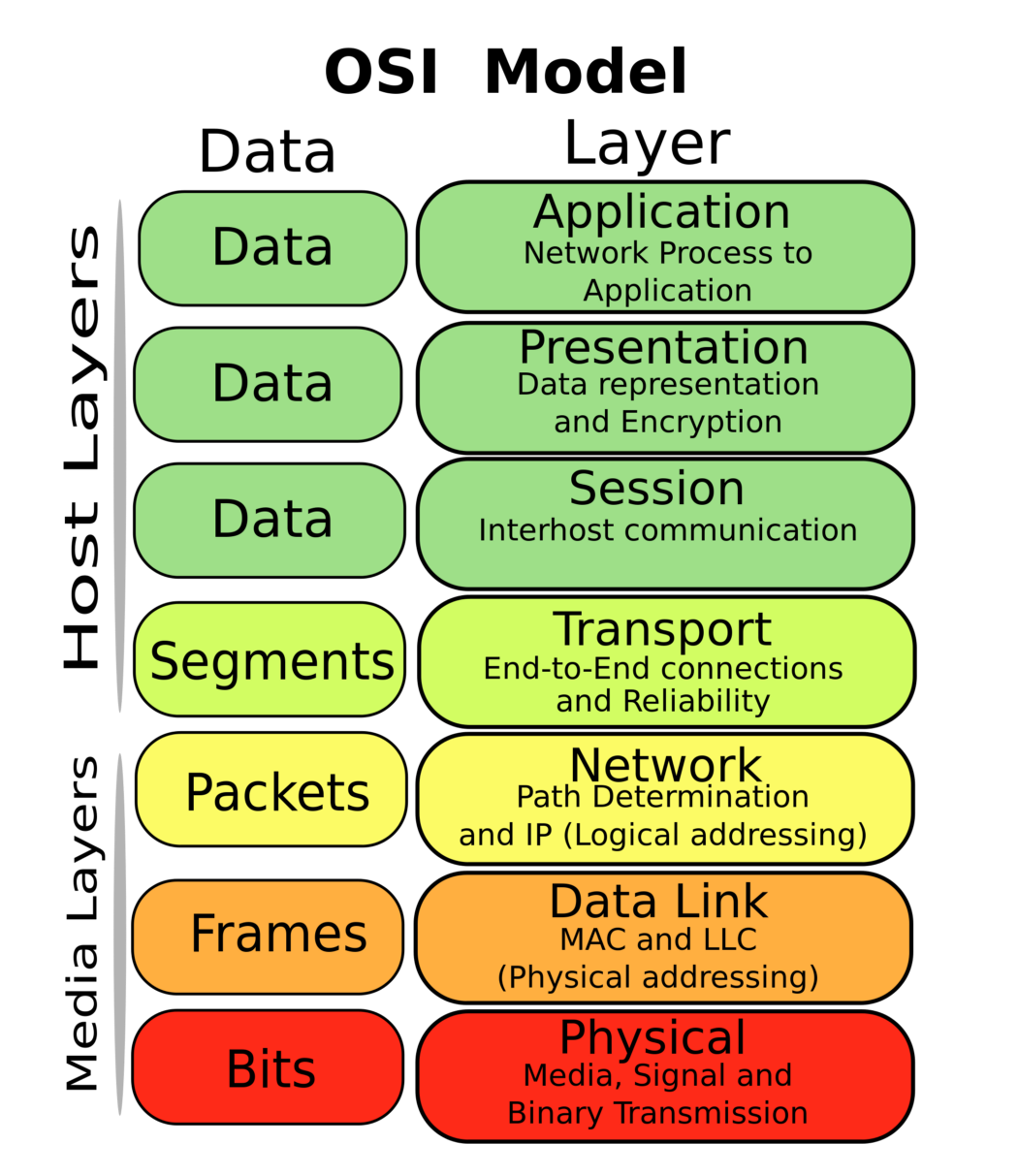

The model has seven layers:

- Application layer

- Presentation layer

- System layer

- Transport layer

- Network layer

- Data layer

- Physical layer

Which can be remembered by either of two mnemonics:

All People Seem To Need Data Processing

or from the bottom up:

Please Do Not Throw Sausage Pizza Away

The Host Layers

The first 4 layers of the model really work at the operating system/software level, within the host:

Application Layer

I found the application layer a tad confusing, it doesn’t concern application programs as such but enables software to access network resources by providing the interface to the layers down the stack. It concerns itself with ensuring that other hosts in the network have the resources necessary to make a connection. It coordinates partnering applications and ensures that data integrity and error recovery procedures are in place. The application layer is only activated when it is apparent that access to the network will be needed soon.

Presentation Layer

The presentation layer presents the data to the application layer. It is responsible for encoding and decoding data ready for transmission. The standard defines how data should be formatted. Data compression, decompression, encryption, and decryption are all tasks fulfilled within this layer.

Session Layer

The session layer is responsible for making sure that requests to the network from applications are only sent to and from that application. It ensures that data isn’t shared with other requesting applications on the host. It does this by creating, managing and removing a session for each application request to the network. It also coordinates communication between systems and defines which mode (discussed in data communication fundamentals the transmission will be: simplex, half-duplex, or full-duplex.

Transport Layer

The transport layer is responsible for inserting data into a data stream and pushing it out from the host onto the network. This is where the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the lesser-known UDP (User Datagram Protocol) do their thing. They are the rules for how to send the data from one host to another.

The key difference is that TCP provides reliable, ordered, and error-checked delivery of a stream of bytes between applications running on hosts, whereas UDP is much more laissez-faire about data stream reliability. UDP is a connectionless protocol, it doesn’t care if the connection is broken, it values latency over reliability.

The Media Layers

The next three layers are known as the media layers and are concerned with actually moving the data between hosts, starting with the:

Network Layer

The network layer concerns itself with figuring out where devices on a network are so that it can figure out the path the data needs to take through the network to get from the sender to the receiver. The network layer manages logical device addressing (IP addresses) primarily through the use of routers.

Two types of packets are used at the Network layer:

Data Packets are used to transport user data through the internetwork. Protocols used to support data traffic are called routed protocols. Two examples of routed protocols are Internet Protocol (IP) and Internet Protocol version 6 (IPv6), (which is next weeks topic, stay tuned folks!)

Route-Update Packets are used to update neighbouring routers about the networks connected to all routers within the internetwork. Protocols that send route-update packets are called routing protocols, and some common ones are Routing Information Protocol (RIP), RIPv2, Enhanced Interior Gateway Routing Protocol (EIGRP), and Open Shortest Path First (OSPF). Route-update packets are used to help build and maintain routing tables on each router.

The route update packets are important as it helps ensure that data packets end up at the right network. I’m going to make up an analogy of how sending a letter would work if the postal service worked like routers.

- I want to send a letter to an address in Plymouth, I live in Birmingham.

- So I send my letter to the Birmingham router.

- The Birmingham router sends the letter to the Plymouth router.

- The Plymouth router checks its network to see if it knows about the host.

- If it does it acknowledges the letter (packet) and sends it out to the Plymouth network for delivery.

- If it doesn’t it drops the letter (packet) and broadcasts an updated route-update packet to the Birmingham router and all adjacent routers.

Routers know about where stuff is by maintaining a routing table. A routing table contains:

Network Addresses. These are protocol-specific network addresses. A router must maintain a routing table for individual routing protocols because each routing protocol keeps track of a network that includes different addressing schemes, like IP and IPv6.

Interface. This is the exit interface a packet will take when destined for a specific network. I.e. whether the packet needs to enter the network behind the router or be forwarded onto another router.

Metric. This value equals the distance to the remote network. Different routing protocols use different ways of computing this distance. Some routing protocols, namely RIP, use something called a hop count — the number of routers a packet passes through en route to a remote network. Other routing protocols alternatively use bandwidth, delay of the line, and even something known as a tick count, which equals 1/18 of a second, to make routing decisions.

Key attributes of a router are:

- Routers, by default, won’t forward any broadcast or multicast packets.

- Routers use the logical address in a Network layer header to determine the next-hop router to forward the packet to.

- Routers can use access lists, created by an administrator, to control security on the types of packets that are allowed to enter or exit an interface.

- Routers can provide Layer 2 bridging functions if needed and can simultaneously route through the same interface.

- Layer 3 devices (routers, in this case) provide connections between virtual LANs (VLANs).

- Routers can provide quality of service (QoS) for specific types of network traffic. You can define that voice traffic takes precedence over data traffic for example.

Data Link Layer

The Data Link layer provides the physical transmission of the data and handles error notification, network topology, and flow control. This means the Data Link layer ensures that messages are delivered to the proper device on a LAN using hardware (MAC) addresses and translates messages from the Network layer into bits for the Physical layer to transmit.

To take our letter from Birmingham to Plymouth analogy further. The router knows enough that the letter needs to go somewhere in Plymouth. Devices in the data link layer know the exact address in Plymouth to deliver the letter to.

The Data Link layer formats the message into pieces called a data frame and adds a customized header containing the destination and source hardware (MAC) address. This added information forms a sort of capsule that surrounds the original message to ensure once it has passed through the internetwork to get to a rough location, the devices in the data link layer have enough information to ensure it arrives at the exact destination.

Each time a packet is sent between routers, it’s framed with control information at the Data Link layer. However, that information is stripped off at the receiving router, and only the original packet is left completely intact. This framing of the packet continues for each hop until the packet is finally delivered to the correct receiving host. The packet itself is never altered along the route; it’s only encapsulated with the type of control information required for it to be properly passed on to its destination.

The data link layer has specifications defined by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). It has two sub-layers:

Media Access Control (MAC) Defines how packets are placed on the media. Contention media access is “first come, first served” access, where everyone shares the same bandwidth — hence the name. Physical addressing is defined here, as are logical topologies. What’s a logical topology? It’s the signal path through a physical topology.

Line discipline, error notification (not correction), ordered delivery of frames, and optional flow control can also be used at this sublayer.

Logical Link Control (LLC) is responsible for identifying Network layer protocols and then encapsulating them, an LLC header tells the Data Link layer what to do with a packet once a frame is received. It works like this: A host receives a frame and looks in the LLC header to find out where the packet is destined — say, the IP protocol at the Network layer. The LLC can also provide flow control and sequencing of control bits.

The IEEE work on standards is done by a number of subcomittees of a project known as 802. The 802 standards apply to different parts of the data link layer but the two most significant ones are 802.3 which defines standards for Ethernet networks and 802.11 which defines standards for wireless networks.

Physical Layer

The last one hooray! The Physical layer does two important things: it sends bits and receives bits and it communicates directly with the various types of actual communication media. Different kinds of media represent these bit values in different ways. Some use audio tones (bring back 56k modems yeah!), and others employ state transitions—changes in voltage from high to low and low to high. Specific protocols are needed for each type of media to describe the proper bit patterns to be used, how data is encoded into media signals, and the various qualities of the physical media’s attachment interface such as electrical, mechanical, procedural, and functional requirements for activating, maintaining, and deactivating a physical link between end systems.

Encapsulation and Headers

That’s all cool but what does this all actually mean in practice? Well, the OSI layers mean that the different functions fulfilled within each layer are encapsulated from one another. Basically, each layer doesn’t need to know how something is done, just that it is done.

When a host transmits data across a network to another device, it’s wrapped with protocol information at each layer of the OSI model. This information is called the header. Each layer communicates only with its corresponding layer on the receiving device.

To communicate and exchange information, each layer uses Protocol Data Units (PDUs). These hold the control information attached to the data at each layer of the model. They’re usually attached to the header in front of the data field but can also be in the trailer, or end, of it.

At a transmitting device, the data-encapsulation method works like this:

- User information is converted to data for transmission on the network.

- Data is converted to segments, and a reliable connection is set up between the transmitting and receiving hosts.

- Segments are converted to packets or datagrams, and a logical address is placed in the header so each packet can be routed through an internetwork. A packet carries a segment of data.

- Packets or datagrams are converted to frames for transmission on the local network. Hardware (Ethernet) addresses are used to uniquely identify hosts on a local network segment. Frames carry packets.

- Frames are converted to bits, and a digital encoding and clocking scheme is used.

And there we have it, a very large summary of how data gets from one computer to another.