I love the agile manifesto, one of the things that most drew me to it was “Responding to change over following a plan”. I’ve worked on enough projects to see the benefit in changing direction when it’s clear that your plan isn’t going to help you hit your goal, and the sheer grinding death-march experience for teams when that doesn’t happen.

However the manifesto doesn’t say much about different types of change and how best to respond to them. I have 3 mental models of change that I’ve seen in teams. I thought I would share as this is fairly early thinking (for me). I’m interested if others have seen these patterns, and what other models I’ve missed.

This is a post I’ll probably come back to and iterate as i’t’s not fully thought out yet, but I want to share something before it’s perfect.

Types of change:

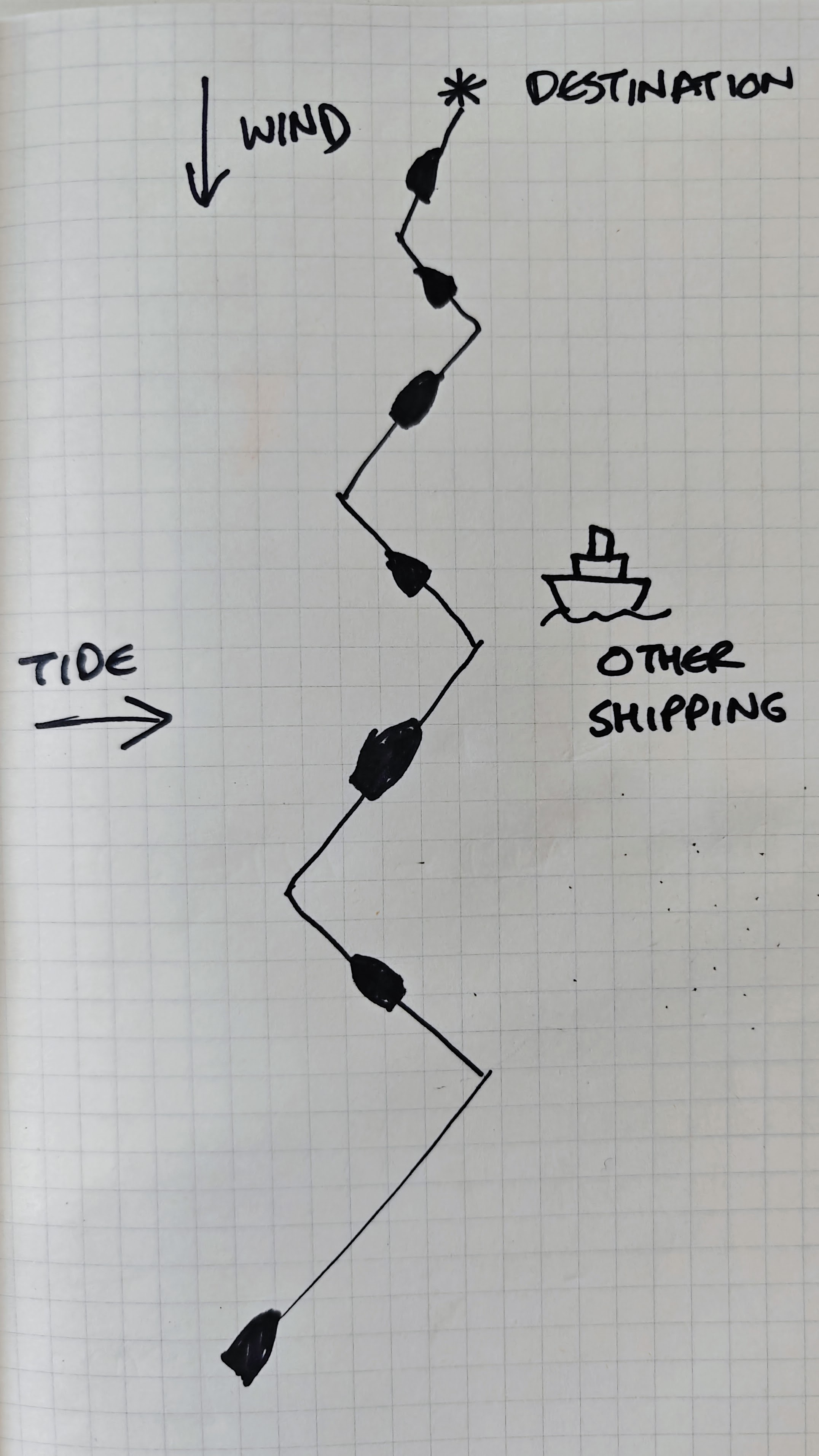

1. The north star ’tacking’ change.

This is the ‘responding to change’ that most agile teams will be familiar with. You have a goal, you set off in a direction to achieve that goal, hit an impediment, or realise you’re not going to meet that goal through measures, and so change direction.

My mental model for this way of working is ’tacking’ you have a known destination, set off on a course to hit that destination, and constantly adjust based on whether you’re on course, or other unforeseen events occur, such as crossing another ship’s path.

In order for this type of change to work of course you need to have a clear goal, and this is often where I see teams struggle. They don’t have a clear outcome they are aiming for, or have no way to measure how they are doing.

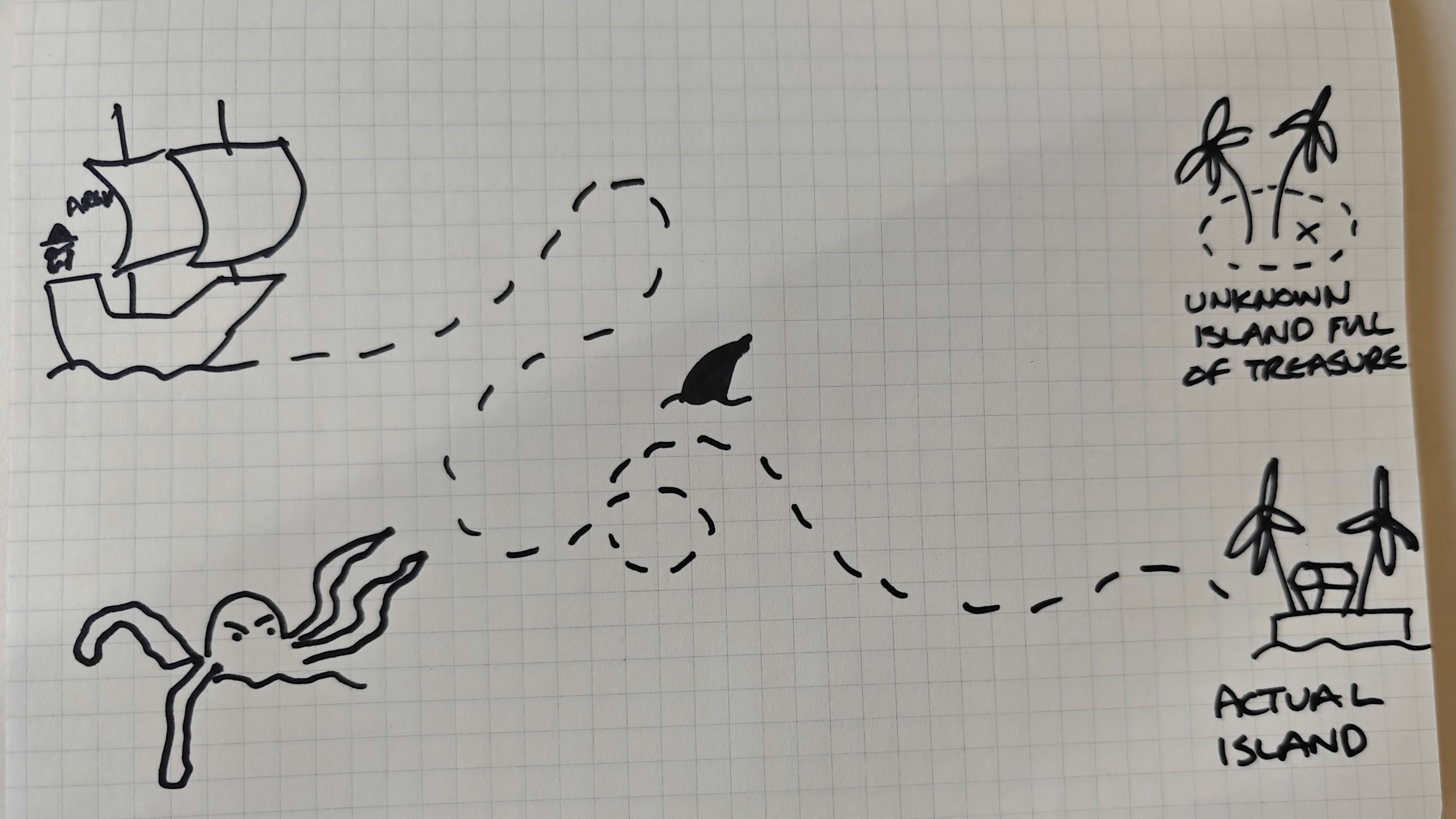

2. The pirate ship dotted-line change.

You know the comedy pirate ship track of a dotted line that does a loop the loop, meets a shark, passes a shipwreck, and eventually arrives upon an island. That’s a common pattern for teams that don’t have a clear destination.

Sometimes that can be viewed as a negative, especially if the team or stakeholders are expecting the team to be aiming for a ’north star’ however it’s a perfectly valid type of change where you may be playing in a space that’s not well understood yet. Exploratory techniques like rapid prototyping, work best here. You’re not building a final solution, your building to learn.

Similarly if teams aren’t explicit that this is the space their in this, it can cause friction. People can view prototypes as the final solution. The team can be asked to clarify operational processes they don’t yet know because they don’t know if this thing is even worth becoming operational. Often people haven’t worked in this way so look for certainty before there is any.

Techniques like tracer bullets in extreme programming can help if you’re in an unknown space and writing software straight away, or adding new unknown capabilities to an existing stack. Writing tests based on assumptions to see what does and doesn’t pass can really help be explicit about what the team doesn’t know yet and how they plan to find out.

3. The Indiana Jones aeroplane montage change.

You know the bit in Indy films where he flies to a new destination and the red line tracks across the map, and at set points changes direction? For me that is very much responding to change by following a plan.

At a predetermined destination, change flights and fly this way for x time. Absolutely nothing wrong with this approach in known contexts, however it’s not the type of ‘responding to change’ that the agile manifesto aimed to address, which was much more trying to talk more about being responsive to the unknown.

That’s not to dismiss what these teams are doing, if they are on a well-known path this is a perfectly valid approach to change, where problems arise are where teams are trying to work this way in a complex unknown environment.

Conclusion

Being more explicit about the type of change you’re doing as a team can help make sure everyone is on the same page about the best delivery tactics to play.

Don’t forget it’s perfectly plausible on large projects that some parts will be more certain than others and it may be necessary to play more than one delivery tactic depending on the problem the team is solving at the time. Don’t assume one way of working will transfer well to different contexts.

Doing an exercise like the good old Rumsfield Matrix at the beginning of a piece of work can help identify what bits of a project are well known versus uncertain, this lets you think more about how you intend to deliver the different bits of the project depending on that certainty.