I love hill climbing and mountaineering, ever since I was dragged up Pen-Y-Fan and got mild hypothermia in the scouts at about the age of 13. One of the best things yomping up hills has taught me is the nature of risk. So I was a bit surprised when I saw this tweet from Vasco Duarte:

Friends, let's collect a list of domains where Risk ELIMINATION is priority #1: Climbing; Air travel industry; what else? #modernAgile #agile #NoEstimates #lean #kanban

— Vasco Duarte (@duarte_vasco) February 15, 2018

I have a lot of respect for Mr Duarte, his work in with the #NoEstimates agenda and his focus on measuring data and forecasting over, estimation and guesswork is interesting and inspiring.

However I couldn’t agree with this point and didn’t make the case well in the limitations of twitter. So in the spirit of cooperation and shared understanding I thought I would describe why I believe risk cannot be eliminated and trying to can actively slow you down and have the reverse effect. Please let me know your thoughts in the comments.

So you’ve decided to go and climb a Mountain.

Good for you, its great to get out into the wilderness, but are you prepared for the journey ahead? At the most basic level have you thought about.

Where you are going and your ability to navigate and walk the route? What the weather is going to do? How much food and drink you’ll need? How long you expect to be out for?

Based on the above you will have packed:

- A navigation aid of some sort

- Appropriate clothes

- Enough food and drink for the duration of your walk

But then you think about all of the risks that could befall you on the walk. What happens if I have an accident whilst I’m out? What if the weather turns bad? What if I run out of water? What if the river I need to cross is in spate? What if I encounter an unexpected terrain or a steep ascent?

So you also pack:

- A comprehensive first-aid kit

- A full set of waterproofs and hat and gloves, just in case the weather turns bad.

- An extra canteen of water

- A rope, harness and basic climbing gear

But now your pack is about half as heavy again and you know you won’t be able to walk at the same speed as with a lighter pack. You’ll be out for longer, so you now need:

- Extra food and drink

You’re pack is heavier again, with a bag this size, the walk is turning into an overnight expedition so you pack:

- A tent or bivouac

- A sleeping bag

- A stove;

- Enough food and drink for an overnight expedition.

And so on.

The process of trying to eliminate all risks has significantly slowed you down and as a result exposed you to other risks:

- A heavier pack reduces your footing on poor terrain increasing your likelihood of injuring yourself.

- A longer trip increases the likelihood the weather will deteriorate increasing the risk of exposure.

Mountain climbing is about trade offs.

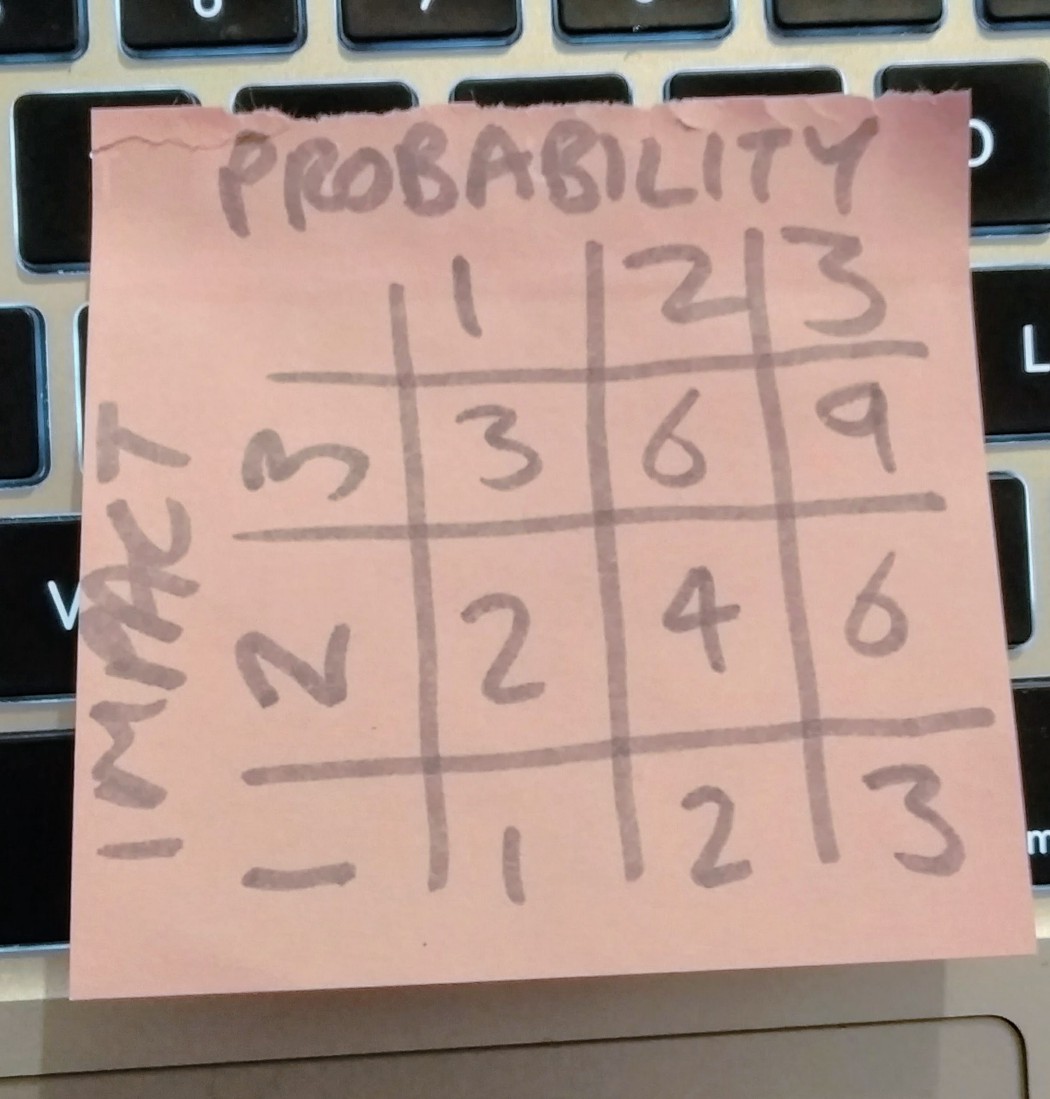

The definition of risk is the impact of an event versus the probability of it occurring.

Risk = Impact * Probability.

Where most risk management fails is in measuring probability effectively, a few methodologies such as Formal Safety Assessment used in the maritime industry and Probabilistic Risk Assessment used in the nuclear industry do this reasonably well by assessing data on previous accidents and near misses, however even this doesn’t handle Black Swan events well.

Coming up with a plan to eliminate all risks without understanding the likelihood of that risk occurring can actively slow you down.

Lets look back at our example. I set off in May in sunshine, the forecast is a windy day with a chance of showers.

There is a high probability of showers, the impact will be I get damp and miserable.

3(P)*1(I) = 4(R)

There is a low probability it will snow, the impact will be I get hypothermia.

1(P)*3(I) = 4(R)

The risk is the same because whilst the likelihood of snow is low, the impact is much higher. So do I take a hat and gloves and a thicker jacket?

No because the extra gear affects the weight I need to carry and therefore energy usage. I make the trade off of lightness and speed (mitigate risk) over preparing for the risk of hypothermia with more clothes (eliminate risk).

These sorts of trade offs happen all the time when out on the hills or climbing, as maintaining speed is a more effective risk strategy than trying to eliminate all risks.

Policies are organizational scar tissue. They are codified overreactions to unlikely-to-happen-again situations.

— Jason Fried (@jasonfried) July 21, 2009

Eliminating all risks, even low probability, high impact ones will reduce your speed, introducing higher probabilities of things going wrong. In my experience, optimising for speed will reduce risk far more than trying to eliminate them all.

Let me know your experiences and thoughts in the comments below.